Paul McNabb has cut five umbilical cords. He once administered care to an Elon student who impaled her leg hopping a fence to a party.

And when not working as a paramedic for Alamance County Emergency Medical Services, he’s in charge of a fire truck a half-hour away, in Guilford County.

He also spends his nights watching Elmo. Because his favorite job position — it's being a dad.First responders are trained to respond to emergencies. McNabb's been conditioned since birth, scrambling around fire trucks as far back as he can remember. Trace two generations back is Grandpa John — he captained the Pleasant Garden Fire Department. His dad, Gary, is the assistant fire chief for the Southeast Guilford Fire Department, and has been in the fire service more than 40 years. His mom, Susan, is a retired Greensboro Police Department officer and his sister, Brianna, is a critical care nurse at Wesley Long ICU. (And can’t forget cousin Jeremy and uncle Jeff — more firefighters.) Last name, all: McNabb.

“We’re a family of givers,” Susan said.

“They supported me one hundred percent,” McNabb said. “At first they wanted me to be a doctor or a major league baseball player — something to make millions of dollars. But for realistic goals — absolutely.”

Paul McNabb's Southeast Fire Department leather fire helmet.

Paul McNabb's Southeast Fire Department leather fire helmet.He’s a third-generation firefighter — now, fire engineer — and a first-generation paramedic. His family history and 11 years as a first responder allow him to provide insight into different high (and low) pressure scenarios — and the climate surrounding the people who navigate them.

“I wouldn’t have it any other way,” McNabb said.

Alamance County Emergency Medical Services (EMS)

A shift in Alamance County EMS is 24-hours on, 72-hours off. As a paramedic, McNabb works alongside EMTs to respond to emergency and non-emergency calls in the county. This Halloween will mark his 12th year in the job.

There are 17 employees on each shift, and there are four shifts. Typical EMT training lasts 3 to 5 months, whereas a paramedic is often a year or more of schooling.

Walking into the West Base — one of three in the county — is surprising to a lay-person. The blacked-out windows and massive industrial garage intimidate, but when the door opens, the first sight is five well-worn recliners and a modest kitchen.

“If we’re not on a call, we’re all here,” said paramedic Lisa Raines. “Some people will hang out here, watch TV. Some will go to their rooms. We try to sleep when we can because we never know when we’re gonna get it. It’s like a big ol' family.”

Raines is also in the family business. She grew up with her parents involved in rescue, but unlike McNabb, who always wanted to fight fires, Raines never thought about being getting involved with Alamance County EMS until adulthood.

“I used to work for Lowe’s Home Improvement. I was always on the lookout for something that I thought I could have a future at. One of the girls I worked with was going to school while we were working together. The more I talked to her, the more I thought, ‘Well, this sounds like fun.’ I decided to get my EMT and my paramedic and I’ve been here 17 years.”

Now, her and McNabb are co-workers at Alamance County EMS.

Forget typical co-worker archetypes — the flatterer, the long-lunch-goer, the water cooler gossip. In the ambulance, it’s "shit-magnets," "black clouds," and "baby magnets."

“I’m pretty good at having a light cloud. I get lots of working calls, I get lots of sick people,” McNabb said. “There are other people who are white clouds that they don’t ever ride any sick people — it’s weird. There’s a man who retired in December who cut 17 umbilical cords. If there was a pregnancy he was probably going to be there, somehow. My big thing — airway. If somebody needs to be intubated, I’m the guy that’s gonna be there.”

“A lot of stuff is low frequency, high fidelity,” said EMT and paramedic-in-training, Lanning Honeycutt. “You’ve got to keep your skills sharp, even pregnancies, which you don’t see every day.”

According to the Alamance County EMS 2018-2019 workload measures, from June to December the average emergency response time was 12 minutes and 36 seconds. Once the ambulance arrives, if McNabb’s driving, the passenger EMT or paramedic will jump out quickly, and McNabb will start to grab the bed or follow inside.

“My initial impression sets the pace for the rest of the time,” McNabb said. “If I went in, and they look sick as crap, then I’m just going to go straight to work.”

Most frequently the emergency calls are for falls. According to the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, the county is home to eight nursing facilities and another 18 adult care homes.

“Gravity is super strong in Alamance County,” McNabb said. Added Honeycutt, “When you cluster those geriatric people all in one spot, that’s the people that are going to use our services. We go to those places a lot — it’s like, ‘Alright, we’ve been there five times today.’”

“If a late call comes in, we just take it,” Raines said. “Do we like it? No. But we take it.”

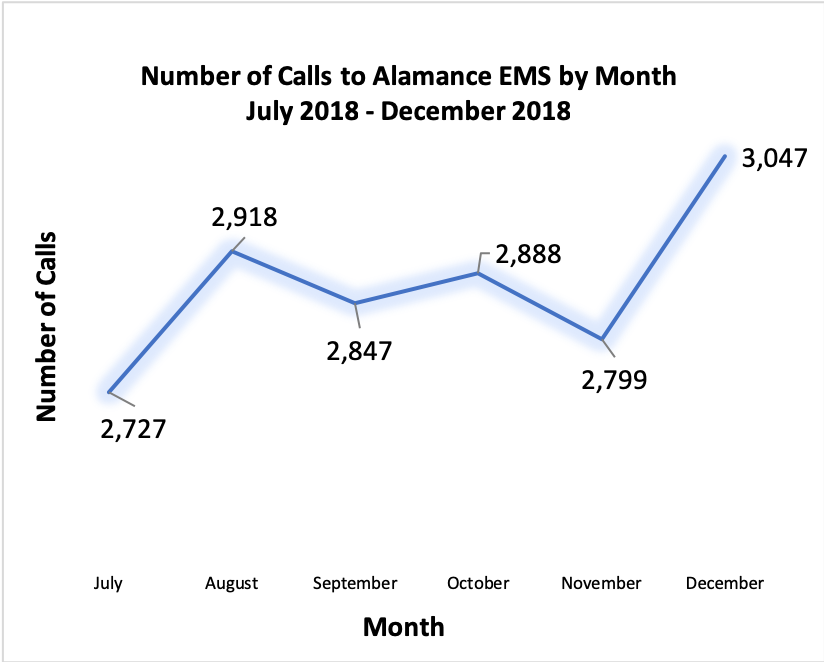

Data from Alamance County EMS 2018-2019 Workload Measures report.

Data from Alamance County EMS 2018-2019 Workload Measures report.As call numbers increase, the need for more equipment does too.

“I know that there's some really cool technology advancements that are being made,” said Hannah Alcock, Elon junior and EMT. “There's automated CPR machines or there's new medications for diabetes or for certain other illnesses or situations that can take place."

The ambulance is home to what McNabb calls, “a defibrillator on crack.” It's worth about $50,000.

“It’s one of those services that a lot of times people don’t appreciate until you need it," said EMT Donald Robinson. It’s just something you don’t even think about until you’re sick or you’re having a bad medical event. They’ll say, ‘Oh my God, I’m so glad you’re here,’ but a lot of times you’re just in the background.”

Alcock took the EMT certification exam on the day she moved into Elon. Though she’d love to work for Alamance County EMS, her experience with emergency services so far has been as an EMT lifeguard in South Carolina.

“I want to say that I treated 145 jellyfish stings in one day at the end of July,” Alcock said.

Elon junior Melissa Menard took EMT courses through Alamance Community College, and did her "ride-along" with Alamance County EMS. During a ride-along, the EMT-in-training rides with an active ambulance crew for 24 hours. Whenever Menard's assigned unit recieved a call from the dispatcher, she would follow along. Her ride-along experience was reflective of the community of nursing facilities and adult care homes — it was mostly elderly people being transported to the hospital.

"It was pretty upbeat, talking to patients who were responding, but also could be very serious and down to business when it needed to be," Menard said. "I learned a lot about the community here, and the relationships that EMTs can have with their patients, especially when we were doing elderly patients transport. They were all very happy to talk and explain about their lives and their situations."

Being a first responder isn't all sirens blaring and hearts pounding.

“I have stayed up all night long,” said McNabb of his EMS paper work. “One a.m. is when I sat down and I got done five minutes ‘til six.”

Alcock says first responders need to have great situational awareness, strong leadership skills, compassion and empathy.

“You'll run into situations where there's a lot more at play other than just treating the patient, whether it's dealing with family members, controlling a crowd or working with other agencies,” Alcock said. “People put a lot of trust in us just by the badge that we wear on our shirt.”

“The biggest thing is capabilities," McNabb said. "We’re not just ambulance-drivers. We get called rescue. We get called ambulance-drivers. If that was the case, then call an Uber. You’d get the same dag-gum result.”

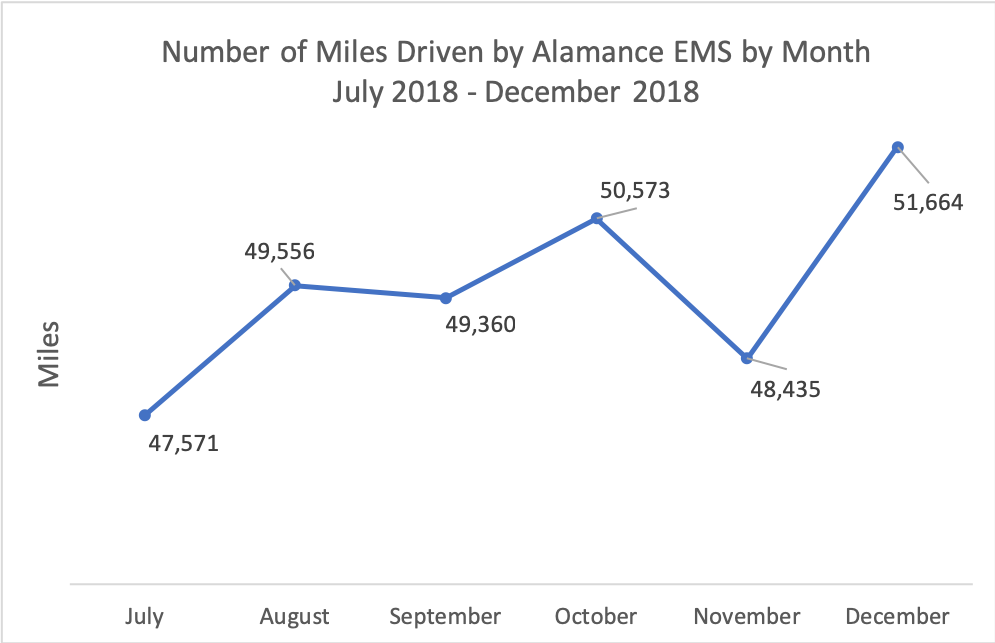

Data from Alamance County EMS 2018-2019 Workload Measures report.

Data from Alamance County EMS 2018-2019 Workload Measures report.

Paul McNabb fills fire truck tanker with water from hydrant.

Paul McNabb fills fire truck tanker with water from hydrant. Adalynn McNabb and her grandma, Susan, enjoy a BBQ dinner made by the Alamance County Fire Department at its annual fundraising event.

Adalynn McNabb and her grandma, Susan, enjoy a BBQ dinner made by the Alamance County Fire Department at its annual fundraising event.